German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier visited Israel two weeks ago and met Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, whose American parents came from San Francisco to colonise Palestine in July 1967. Bennett has boasted: "I've killed lots of Arabs in my life and there's no problem with that.”

In preparation for his visit, Steinmeier actively defended Israeli officials from being prosecuted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for colonial war crimes. He asserted that "the German government's position is that the International Criminal Court has no jurisdiction in this matter due to the absence of Palestinian statehood”. Outgoing Israeli President Reuven Rivlin has thanked Steinmeier for Germany's commitment to Israel's security and for opposing the investigation.

Germany has indeed been one of the most implacable enemies of the Palestinian people and their struggle against settler-colonialism since the 19th century

Steinmeier, in the tradition of all post-war West German governments, explained Germany's unwavering support for Jewish colonisation of Palestine because of the guilt it carries: "Germany lives with the historical legacy of the monstrous abuses of political power perpetrated by the Nazi regime.” That the post-WWII German political culture acquired a conscience about the genocidal murder of European Jews is amply clear, but it does not seem to have acquired much of a conscience about Germany's other colonial and genocidal crimes since it was unified in 1870-71, and they are many.

Steinmeier's remarks were denounced by (en.abna24.com news hamas-pa-slam-germany-for-opposing-icc-probe-into-israeli-war-crimes - expired link (before 2023-02-01) ), Hamas spokesperson, who said that Steinmeier "encourages the occupation to continue its crimes and aggression, and places the [Israeli] regime above international law”. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine described the German president's remarks as "shameful and arrogant” and "an invitation for Israel to perpetrate more crimes”. Even the - expired link (before 2023-02-03) en.abna24.com → Palestinian Authority; described them as a "departure from the rules of international law” and an "interference in the work of the ICC as well as its rulings”.

Germany has indeed been one of the most implacable enemies of the Palestinian people and their struggle against settler-colonialism since the 19th century. Its contributions to the colonisation of Palestine have been ideological, financial, physical and military.

Settler-colonies in Palestine

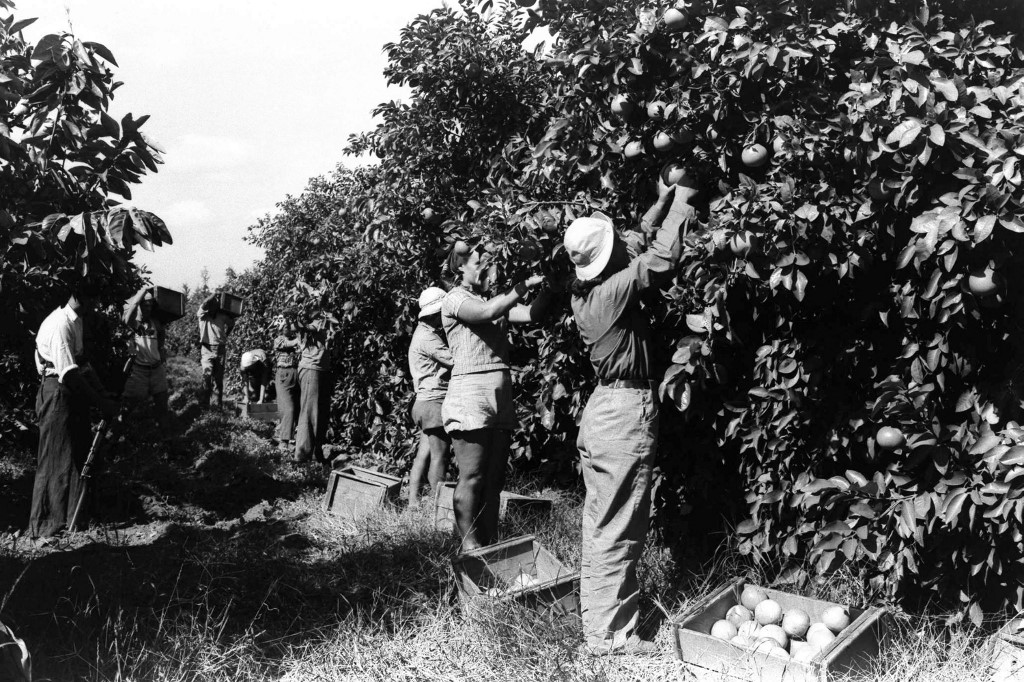

A decade before Germany embarked on the colonisation of Africa, a small group of Germans expelled from the Lutheran Church for their millenarian beliefs reorganised themselves in 1861 as German Templers, and embarked on establishing settler-colonies in Palestine. The first was established in 1866 near Nazareth, and in 1869 they built a colony in the Palestinian city of Haifa. Three more colonies followed, including Rephaim, near the Old City of Jerusalem.

During the Ottoman-Russian war of 1877-78, German war ships came to the shores of Palestine to defend the German colonists in case they were attacked, and in the process, the German consul forced the Ottomans to recognise the Templers' colonies, which they had previously refused to do.

Indeed, the Templers had wanted to turn Palestine into a Christian state, and were hoping that it would be awarded to Germany at the end of the war. When the 1908 uprising of the Young Turks erupted in Constantinople, Palestinian peasants attacked the German colonies and Zionist Jewish colonies. Again, the Germans dispatched a warship to Haifa.

Kaiser Wilhelm visited Palestine in 1898. A member of his entourage, Colonel Joseph Freiherr von Ellrichshausen, decided to form a society for the advancement of German colonies in Palestine and to extend credit to them. With the new money, in addition to Wilhelmia, the new wave of Templers built the colonies of Walhalla, Bethlehem of Galilee, and Waldheim in the early 20th century.

On the eve of WWI, there were close to 2,000 Templers in Palestine. In the 1930s, many of the colonists supported the Nazi regime and were ultimately chased out by the British and the Zionists, who took over their colonies.

Model for Zionist efforts

Earlier, in 1871, newly unified Germany was in the throes of plans to colonise its eastern provinces, which had a majority Polish population. A Prussian Colonisation Commission was established to Germanise the provinces of West Prussia and Posen through colonisation and the suppression of Polish national identity. By 1914, the commission was able to transplant about 155,000 people to hundreds of small German settler-colonies, but resistance from Polish landlords, who established their own settlement organisation, effectively defeated the German efforts.

German colonisation of Posen became a model for early 20th-century Zionist efforts to colonise Palestine. The Palestine bureau of the Zionist Organization was headed by the German Jewish and Posen-born Arthur Ruppin, who had witnessed "the permanent struggle between the Polish majority living on the land and the dominant, mainly urban, German population”.

Two weeks after his arrival in Palestine in 1907 to explore Jewish colonisation of the country, a trip funded by the Jewish National Fund (JNF), Ruppin wrote to the JNF: "I see the work of the JNF as being similar to that of the Colonization Commission working in Posen and Western Prussia. The JNF will buy land whenever it is offered by non-Jews and will offer it for resale either partly or wholly to Jews.”

Ruppin created the Palestine Land Development Company (PLDC) in 1908, whose work, according to its founding document, would assume the methods used in the German colonisation of Posen. Zionist leader Otto Warburg explained that the PLDC did not "propose new ways, new experiments whose nature is unknown. We assume instead the Prussian colonization method as it has been practiced in the last ten years by the Colonization Commission.” Warburg had been himself a member of the Prussian Colonisation Commission and became the president of the ZO from 1911 to 1921.

Meanwhile, German settler-colonisation and genocidal massacres had proceeded apace especially in Namibia and Tanganyika. In Tanganyika, between 1891 and 1898 the Germans killed upwards of 150,000 Wahehe who had revolted against German colonialism, and in Namibia between 1904 and 1907, they killed at least 65,000 Hereros (about 75-80 percent of the Herero population), and 10,000 Namas (35-50 percent of the Nama population).

After WWI, and the loss of German settler-colonies in Poland, and across Africa and the South Pacific, the Weimar Republic tried - but failed - to restore German sovereignty over them at the League of Nations.

Palestinian dispossession

The Weimar regime's policy towards Jewish colonisation of Palestine was manifest early on. While the majority of German Jews opposed Zionism (no more than 2000 German Jewish colonists, mostly Russian Jewish immigrants to Germany, went to Palestine between 1897 and 1933), the Weimar Republic quickly supported the Balfour Declaration, and after joining the League of Nations in 1926, became an active supporter of European Jewish colonisation in Palestine.

The Nazis proved no exception to the German commitment to settler-colonialism in Asia and Africa, although the Nazis mainly targeted eastern Europe. Nazi antisemitic policies in the 1930s were in fact instrumental in increasing the pace of Zionist colonisation of Palestine. During the first few months of the Nazi regime in 1933, the Zionist movement signed an agreement with the Nazis to transfer the funds of Jews leaving the country to Palestine, an agreement that remained in effect until 1939.

The deal facilitated the transfer of about $40m of German Jewish wealth to Palestine by 1939 - a substantial amount for the Zionist movement, which used the funds to further the colonisation of Palestine and the dispossession of its indigenous people. Indeed, 60 percent of all capital invested in Palestine between 1933 and September 1939 came as a result of the agreement.

At the League of Nations, Germany's representative reassured members in October 1933 - days before Nazi Germany withdrew from the league - that the government was making every effort to "ensure the smooth emigration of Jews from Germany to Palestine”. These efforts were supported by Germany's consul general in Jerusalem, Heinrich Wolff, who secured in the summer of 1934 a loan of 100,000 Palestinian pounds for the Jewish colony of Netanya to purchase German machinery.

As head of the Jewish department of the SS's secret service, Leopold von Mildenstein was a hardened Zionist. He had returned from a six-month visit to Palestine in the 1930s singing the praises of Jewish settler-colonialism. He published a 12-part report in Joseph Goebbels' Der Angriff, the propaganda organ of the Nazi party, in praise of the Jewish colonies: "The soil has reformed [the Jew] and his kind in a decade. This new Jew will be a new people.” [ □ comment: Just like the Zionist idea of a new people: meaning having thrown overbord most of what Judaism entails. ]

In May 1935, the head of the SS Reinhard Heydrich himself wrote an article in Das Schwarze Korps, the official organ of the SS, in which he extolled the Zionists: "The Zionists adhere to a strict racial position and by emigrating to Palestine they are helping to build their own Jewish state…Our good wishes together with our official good will go with them.”

'Valuable service'

Haganah agent Feivel Polkes was dispatched to Berlin in 1937 and partnered up with von Mildenstein's protege, Adolf Eichmann, as his negotiating partner. Polkes thanked Eichmann for the Mauser pistols and ammunition the Haganah had received from Germany between 1933 and 1935, which "rendered valuable service” to the Zionist militias in shooting Palestinians during the latter's anti-colonial revolt that erupted in 1936.

The Zionists invited Eichmann and Herbert Hagen, also of the SS, to visit their colonies in Palestine, where they arrived in October 1937, disguised as journalists. Upon their arrival, Polkes took them to Mount Carmel and to visit a kibbutz. Eichmann would reminisce in his hideout in Argentina decades later that he was most "impressed by the way the Jewish colonists were building up their land”. He averred after his visit that "had I been a Jew … I would have been the most ardent Zionist imaginable”.

All in all, around 50,000 of the approximately half a million German Jews left to Palestine between 1933 and 1939.

Following the establishment of West Germany after WWII, every government (and every German government since reunification in 1990) continued the German pro-settler-colonial policies, that never abated since the 1870-71 unification, regardless of the type of ruling regime - with the major exception of East Germany during the GDR period. As Steinmeier would later do, West Germany justified its alliance with Zionism and Israel after WWII as a form of compensation for the genocide that the German people helped the Nazi regime perpetrate.

West Germany supplied Israel with huge economic and military aid in the 1950s and '60s, including tanks, which Israel has used to kill Palestinians and other Arabs. Since the 1970s, the Germans have also provided Israel with nuclear-ready submarines; in recent years, Israel has armed German-supplied submarines with nuclear-tipped cruise missiles.

Ongoing enmity

In 2012, Ehud Barak, then Israel's defence minister, told Der Spiegel that Germans should be "proud” that they have secured the existence of the state of Israel "for many years”. That this makes post-1990 reunified Germany an accomplice in the dispossession of Palestinians is of no more concern in Berlin than it was in the 1960s to West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who affirmed that "the Federal Republic has neither the right nor the responsibility to take a position on the Palestinian refugees”.

This is to be added to the billions of dollars that Germany has paid the Israeli government as compensation for the Holocaust, as if Israel and Zionism were the victims of Nazism, when in reality it was European Jews who refused to colonise Palestine who were killed by the Nazis.

Germany's longstanding backing of Israel ... [is] also crucially informed by German colonial racism towards non-white colonised peoples worldwide

Since the late 1960s, West German governments have denounced Palestinian resistance to Zionist settler-colonialism as "criminal” and "terrorist”. They banned Palestinian solidarity organisations, including the - expired link (before 2023-02-25) (commentarymagazine.com) General Union of Palestinian Students.

After the 1972 Munich massacre of Israeli Olympians, the West Germans activated their racist "Alien Law” for the massive deportation of Palestinian workers and students from the country, based on "an outright lie" that they supported the Munich attack, which they did not.

Since 1990, reunified Germany's enmity towards Palestinians has continued steadily. Ironically, Steinmeier's remarks in support of Israeli settler-colonialism were made days after Germany finally acknowledged its colonial-era genocide in Namibia.

Given its illustrious support for settler-colonialism around the world, Germany's longstanding backing of Israel and Zionist settler-colonialism - and for a proud killer of Arabs, such as Bennett - do not only derive from its professed guilt over the genocide perpetrated by the German people under the Nazi regime, but are also crucially informed by German colonial racism towards non-white colonised peoples worldwide, who, as far as Germany is concerned, were always dispensable in the interest of white settler-colonialism.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.